Douglas KAHN: Could you tell me how you got involved in Central American politics?

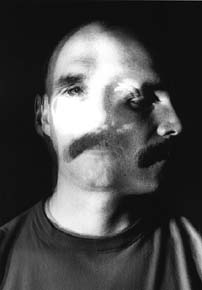

Bob OSTERTAG: While in New York through the late 70s, I was getting more and more politically involved in various things and then after Somoza fell, I went to Nicaragua in 1980 to see if I could arrange to put out some Nicaraguan music in the United States on the label Fred Frith and I were running called Rift. It completely turned my head around, and the record never came out and I never played another note of music for almost 10 years. The last concert I did was 1981, but even by then I hadn't performed for a long time, I was just doing El Salvador work. I had one gig left in London and at that last gig my Serge blew up so that really settled the question.

Douglas: You should have had a Serge protector! Weren't you involved in CISPES (Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador)?

Bob: Yeah, I was one of the original members, on the national executive committee and for a while I was the East Coast roving organizer. I traveled all around the East Coast and then they put me in charge of all of their printed material. I published their newspaper, did research and public speaking, but after a while I had a big falling out and I decided around 1984 I would work directly in El Salvador. I began freelancing as a journalist and writing mostly for left-orientated newspapers, but also for the San Francisco Chronicle. I was also associate editor for Pacific News Service, which is a small alternative wire.

Douglas: What steered you back to music?

Bob: A combination of things, mostly just realizing there really wasn't very much political space for me, but also asking myself is this what I am going to do with the rest of my life? I wasn't prepared to burn all my bridges.

Douglas: You came back with almost a decade of political activism behind you. Was that the source of reality music?

Bob: Pretty much, but my political activism went back before that to the end of the 1970s, when I was doing pieces which used news clips in a semi-journalistic way. There's also material from the TV incorporated into them as in "Voice of America" with Fred Frith, and by the time we did the gig in London I was using tapes I had recorded myself in Nicaragua. It's common now for people to appropriate material from the mass media, back then it was a bit more novel.

Douglas: Could you talk about "Sooner Or Later"?

Bob: The sound source is a recording of a young boy in El Salvador burying his father who was killed by the National Guard because he was a guerrilla sympathizer. It's an actual recording of him at the grave. He is talking about what his dad meant to him, things he and his dad used to talk about and the last thing he says is "Sooner or later I'll get the bastards who did this," and that's where the title comes from. There are three sounds that you hear on the tape: the sound of the boy's voice, the sound of the shovel digging the dirt for the grave, and the sound of a fly buzzing in the air. Everything is made out of those sounds. I wanted to blow it up big and envelop people in it.

Douglas: How do you make it bigger?